When a crisis strikes, there are many actions organizations must take to minimize the impact on your business. In a recent webinar, Successful Crisis Management for Your Organization, Regina Phelps, Founder, Emergency Management and Safety Solutions, touched on five initial topics that you must consider when your organization experiences a crisis:

- People – The most important asset to any company is its people. A crisis could put these people in danger. Make sure your crisis management team can answer the following: Are lives in danger? Is there a life safety issue? Is there an impact to your employees, customers, vendors or visitors?

- Facilities/Critical infrastructure – To keep your business running, facilities and critical infrastructure must be checked on. Even if the buildings haven’t been impacted yet, are they at risk?

- Technology – Another critical aspect of your business crisis management teams need to consider is technology. Is there a disruption of services (i.e. telecom network, data centers)? Is there an information security issue?

- Business – In any crisis, you’ll want to be sure that your organization can continue to perform mission-critical business activities to minimize the impact. Is the crisis impacting your customers? Is it having a significant financial impact on the company?

- Brand reputation – When a crisis hits there is always the chance your organization could face extreme fallout in relation to its reputation. For this reason, it is important that crisis management team members respond quickly as a major hit to your reputation could significantly impact your organization for years to come.

If you’d like to learn more about how your organization can successfully manage a crisis, watch the full webinar by Regina Phelps, “Successful Crisis Management for Your Organization.” You can access the slides and follow along with the transcript below.

Webinar Slides

Webinar Transcript

William Penfield:

All right, let’s get started. Once again, thank you for joining us today. My name is Will Penfield and on behalf of Everbridge I’m excited to present this webinar, Successful Crisis Management for Your Organization. During the event Regina Phelps will discover disaster lessons, options to organize your team, and the four essentials of crisis management. Following Regina, we will cover critical event management and how it relates to managing [00:00:30] a crisis at your organization.

After the presentation, we will have a short Q&A session with our speaker. We encourage everyone to participate and ask questions during the webinar. You could submit your questions by typing in the questions widget, and submitting it to all panelists. Links to the slides and recording of the webinar will be sent out to all registrants by the end of the week. You can also look for a link to the recording for all our webinars on everbridge.com under our resources section.

I would like to introduce [00:01:00] you to our speaker, Regina Phelps, it’s an internationally recognized expert in the field of emergency management and continuity planning. Since 1982 she has provided consultation and educational speaking services to clients in four continents. She is founder of Emergency Management and Safety Solutions, a consulting company specializing in incident management, exercise design, and continuity and pandemic planning. Clients include many Fortune 500 companies. Mrs. Phelps is a frequent top-rated speaker at well-known [00:01:30] conferences such as the Disaster Recovery Journal, CP&M, and the world conference on disaster management. She is frequently sought out for her common-sense approach and clear and clean delivery of complex topics. Following Regina, you’ll hear from me, William Penfield on critical event management and how it relates to successfully managing a crisis at your organization.

Now before passing it over to Regina, I want to give you all something to think about while she discusses how your organization can successfully manage a crisis. [00:02:00] Think about all the incidents that can impact your business in any given year, from severe weather and active shooters to IT downtime and cyberattacks. These incidents can have a significant impact on your business and ultimately in 2016 companies lost $535 billion as a result of these types of incidents. Now when one of these incidents occurs, a major challenge to your organization may be information coming from multiple different sources and tools. Compiling all this information can be very time-consuming [00:02:30] and create a lack of actionable insights, ultimately delaying resolution and increasing operational risk.

Now what if you could have all the necessary information silos and data in a single pane of glass and then be able to act swiftly on this information to keep your people safe and your business running? That’s just something to think about while you listen to Regina’s presentation today. With that I’d like to pass it over to Regina to begin her presentation. Regina, you may begin.

Regina Phelps:

Great. Thanks very much Will. It’s a real pleasure to be here today to talk about [00:03:00] how to successfully manage a crisis in your organization. My belief is that there’s essentially four skills that we all need to possess in order to be able to successfully manage any crisis, and my job today is to inspire you and your company to make sure that your teams possess all four. Today what I’m going to be talking about first of all are some disaster lessons, I want to talk about the options that you have to organize your team, and then I do want to talk about the four essentials, and then we’ll conclude [00:03:30] with some successful crisis management.

Let’s talk about this whole concept of disaster lessons for a moment. These are things that I’ve actually seen in the last 35 years that I’ve been in practice, their mistakes that our clients have made, and others have made, and hopefully you’ll learn about them and not make them yourself. Let’s begin first of all by looking at the first one, declare the disaster and activate as early as possible. One of the things that I discover in my clients is [00:04:00] that many times they are very reluctant to actually declare the disaster, even reluctant to call a team together in order to begin the process of even assessing an incident. Be sure that you activate early and then staff up to a high enough level.

Another problem I’ve seen is that during an emergency, maybe it’s a building evacuation, everybody is left to go home, and then all of a sudden the crisis team realizes, “Oh my gosh. We don’t have the right people. We don’t have enough people. We might need more administrative support, [00:04:30] technology support,” and they are short-staffed. So make sure that you have enough staffing before you let people go.

Then what you want to do is you also want to make sure that you’re issuing clear and consistent instructions to staff. How do you let people know what they’re supposed to do? Where they’re supposed to go? What they’re supposed to do as far as their work is concerned? Is the building open tomorrow? Be clear and consistent because if you don’t say things in that kind of manner, they’re going to make things up on their own.

[00:05:00] It’s also critically important that you delegate authority to those people who’ve been asked to do the job. Sometimes what I find is people are given their responsibility to do a job, but they’re not given the authority, and they’re asked to come back and say, “Can I? Can I? May I? May I?” In a crisis that’s not what you need. You give somebody authority and a responsibility, and then if there are issues, you deal with it at the time, but don’t handcuff people because you haven’t given them the responsibility and the authority.

[00:05:30] You also want to make sure that you understand that over time the plan will degrade and that’s not just the plan but actually even team members as well. Think about it from this perspective, is that many of us never have activations that last very long, and knock on wood, that’s really a great thing. But what happens is that we never think that our plans will be activated, pardon me, for days, or maybe even weeks. Certainly know that after the first 24 hours the team is going to be tired, the plans may not be that well thought [00:06:00] out for after the first 24 hours, and effectiveness will certainly suffer, so you want to make sure that you have something in place to monitor.

Then what you want to do is you want to also then consider two common syndromes. These are two of my favorites, which I’ve heard many, many, many times in my practice. Been there, done that. Be very suspicious of yourself or others who think they know everything about the emergency that’s in front of them. “ [00:06:30] Yeah, I know what a hurricane looks like. Yeah, I’ve been through an earthquake.” When you start hearing people talk like that, you need to pay attention because they’re not looking at all the things that could go wrong in this particular situation. Be aware of that kind of cognitive bias. My favorite, which I hear actually from a lot of my university clients is, “We’re a really smart group and we’re just going to figure it out when it happens.” A bunch of PhDs in a room saying, “Yeah, we’re smart, and we don’t need a plan, we don’t need practice because we’re smart.” [00:07:00] No, you need all of this.

The key thing that leaders need to understand in a crisis is you have to make decisions, even if the information is incomplete, and you have to keep moving the group forward. That is your job in crisis management, make a decision, move forward. If decision is wrong, make another one. Keep moving the group and the issue forward.

Also, be very aware of situational awareness. I’ll talk about this in a little bit, but I cannot [00:07:30] emphasize enough. We’re going to be making all kinds of decisions on information, and we need to have many ways to get information to us. That’s called situational awareness. Social media, traditional media, emergency responders, employees, clients, vendors, who are your sources of information, how do you receive that information, how do you validate it, and then how do you present it in a way that your leadership can actually digest it and make decisions?

Communication, critical, communicate, communicate, communicate. [00:08:00] In all of my years of practice I’ve never had somebody say to me, “Oh my gosh. My company communicated too much with me in that disaster.” You’re never going to have that. My last lesson is one that is a more recent lesson that’s been in the last few years and it certainly seems to happen every time you turn around, and that is this, social media. I want you to repeat after me, I will never, ever, ever, ever forget about social media, and the power of an individual [00:08:30] to change my company’s life forever.

I want [00:09:00] you to really think about this. I will never, ever, ever forget about social media, and the power of an individual to change my company’s life forever. Of course all you have to do is simply remember the most recent kind of egregious act of social media. That was certainly the presentation of the United passenger being dragged off a plane on April 9th from Chicago to Louisville. All you have to do is think about that one particular incidence and realize how incredibly devastating this [00:09:30] will be for United, for anybody who has this situation. Boy United has not been able to get out of their own way. I’m sort of embarrassed because I’m actually a two and a half million mile flier on United and I feel really sad for all of the employees, but boy, they still make mistakes.

I want to show you an actual letter I got from United. Actually it was an email and it’s actually kind of funny because you won’t believe what the subject matter line was in the email. “Actions speak louder than words.” [00:10:00] Oh my gosh. This came out two weeks after the actual incident, and I can’t believe they would actually select that particular subject matter line. Of course there was tons of protest all over the United States in airports and there’s been many other issues, lawsuits and otherwise about this one particular incident. Not to mention lots of humor. This has actually been one of my favorites. These are all of the different apologies that United [00:10:30] made, and a few that there are some made up at the bottom, but it gives you an idea about how when you make a mistake and it’s broadcast by social media that it is a crisis that you will live with for a very long time.

Let me briefly talk about the options to organize your actual team, because people first of all kind of stumble on how do I even get started with organizing a team to begin with. Essentially you all, you should have probably two teams. If [00:11:00] you have a company that’s over about 1,000 people, you should have a tactical team that’s managing the tactical response activities, that’s representing the key departments, and then there’s a strategic team that is usually comprised of senior executives. The question really for your tactical team is, how is it structured? Do you utilize your usual reporting structure? Is it the incident command system or is it something else?

I want to talk about those two options in particular, your usual [00:11:30] reporting structure or the incident command system. Your usual reporting structure the big plus about that is it’s what you know, it’s what you use every day, and it’s your usual organizational chart. But there’s actually some downsides in that actual reporting structure in a crisis, and here’s a few of them for you to think about. The first of is the span of control may be too large to be effective. If you have one person who’s in charge of the team, whatever title you’ve given them, if they [00:12:00] have, think about the number of departments that might be there, legal, HR, facilities, IT, all the key lines of business, communications, finance, regulatory compliance, there’s a lot of folks. That’s a lot of people for one person to actually hear from. So the span of control is likely too large.

There also will be likely very lots of silos at your traditional silos of your business, and sometimes it’s too many to be effective. Because of those silos there actually could be duplication of effort or [00:12:30] things could get completely missed, and that’s another issue. Because of that also there may not be clear authority. You need literally a single person if you will who’s running the ship versus all of those silos and reporting that to their usual reporting structure. Sometimes your usual methodology isn’t going to work. I’ll talk more about the incident command system in a version of that to give you an option.

The reason this is so important for you to think out as far as your structure is concerned [00:13:00] is that what you’re looking for in any crisis is what we call the six Cs, command and control because that’s what we’re doing this for, secondly, is the ability for you to collaborate not only internally but externally with other groups and also with other locations, and then the issue of coordination, how you can coordinate effectively with yourself internally but also others, how you communicate and what you’re looking for of course ultimately is a consistent response.

Keeping those things in mind let’s talk about the four essentials [00:13:30] for a moment. I view these as critical, and if you’re going to be effective in crisis management, you have to nail these. First of all, you need to understand your roles and responsibilities. Secondly, you have to have a clear assessment process, a team and an escalation strategy. Third, you need to know how to build an action plan. Then lastly, you have to be able to develop timely and responsive communications. If you don’t have these four things, you are going to stumble right out of the beginning moments of the crisis [00:14:00] and it’s going to take you a while to right yourself. That’s what I’d like to have you all avoid.

Let’s talk about team structure roles and responsibilities for a moment. I alluded to that just a moment ago when I talked about how you were organized, but I want to talk just briefly about the incident command system. It’s a methodology that’s used in crisis management and has been used successfully for about 35 years. It was born out of my state, California, when a series of wildfires were handled very poorly in the 1970s [00:14:30] and is now used essentially all over the world. It’s used in every public and private sector that you can imagine across the world and it’s required for all governments in the United States, city, county, state, federal, all agencies, all disciplines. I’ve taught it in four continents and it’s a highly effective system.

Now you may say, “I don’t want to change,” and I’d say, “Okay great, I understand that, but there might be some benefits about how you organize within this structure.” That’s why I wanted to explain [00:15:00] the ICS model, just for a second. Again, since 2005 everybody uses it, so every police officer that comes to your facility, every firefighter uses this and they know it. It’s essentially comprised of these teams in front of you. What I want you to think about is even if you use your normal kind of structure, can you organize folks into buckets? Let me explain quickly what these buckets are.

The command post if you will at the top, that’s often called an incident commander. That individual is responsible [00:15:30] for the entire tactical recovery of the organization and reports directly to the executives. Our communications team, which might be comprised of social media, regular communications, marketing, government relations, lots of folks who are communicators live in that comms box. In a corporate operations team you’re likely to see the individuals who are responsible for the backbone recovery of the organization. What does that mean? Facilities, security, technology, everything [00:16:00] we need to do in order to work.

Logistics is usually comprised of HR and a public sector team. You’ll also find procurement there, but we find it doesn’t work very well in a corporate setting and it’s usually in finance for us. Planning and intelligence, all the key lines of business, legal, regulatory, compliance, business continuity, all those folks would have to work together to manage and recover the organization. Then lastly finance, so that could be AP, AR, general ledger, risk, insurance, [00:16:30] procurement, payroll, all those key things.

Just briefly when you look at this structure, if you kind of group everybody together in teams, they should all have a team leader in front of every one of those boxes, and they are the ones that report to the incident commander. Instead of having 20 people tell the incident commander what’s going on, you only have four, plus the communications team. So it’s highly effective. There’s lots of information about ICS and I have lots of lectures that I’ve done for Everbridge and others for this. I just wanted to have you think about [00:17:00] a different way of organizing, even if you don’t call it ICS, and even if you don’t use a lot of that methodology it’s really helpful.

What I want you to think about all with your team and structure and roles is that you need to make sure that your plan clearly calls out what are the roles and responsibilities of every single person on your team, and every person who’s on your team should actually have a checklist so they know what their job is. Now you may say, “That seems kind of silly. Why would I do that?” Well, think about it from this perspective? What if they don’t come? [00:17:30] What if their backup doesn’t come? It could be after an earthquake or a hurricane or something like that. You need to hand a checklist to somebody and say, “I need you to do this.” That’s why checklists are awfully helpful. Also, it just reminds us in a crisis when we’re kind of frazzled everything we need to do and it’s a great way to check off things to make sure that you’ve actually done what you’re supposed to do.

Then you want to make sure that your plans and checklist stick your expected risk profile, your likely activation. [00:18:00] Look at your hazard risk analysis. What are you expecting to happen? Earthquake, hurricane, tornado, floods, active-shooter, any of those things. Make sure that it all fits. We are advocating an all-hazards plan, but make sure that things that are in there are going to fit an all-hazards approach.

Then you might be wondering, “Well, if those folks are doing all that stuff, what are the executives doing?” That’s really the strategic team and they essentially have four really critical jobs and they are not what the other folks are working [00:18:30] on. They are, and ideally they’re not part of the tactical crisis management team, unless you’re a really small company, because they have critical jobs. I will tell you, executives have a tendency to gravitate towards the tactical activities because it’s fast-moving, it’s critical, it needs to be done right away, and frankly tactics are easy to gravitate to. Strategy is much harder. They have four jobs in my opinion and these are the things that we train executives that they [00:19:00] must be doing at time of crisis.

The first one is providing strategic and policy oversight. They’re the ones that are going to make all kinds of decisions. Do employees get paid or not? Do we open tomorrow or not? What do we tell the analysts on the street? How are we going to be talking with our big customers? What is our overall policy about a particular issue? Are we doing refunds? I mean the list goes on and on. Those things need to be done by these individuals, and a lot of those have to be done pretty soon. They also are the ones that are going to approve expenditures [00:19:30] for large purchases. Your tactical team probably has a signing authority of a certain amount. Maybe it’s 50,000 or maybe it’s 100,000, but big expenses beyond that, they’re going to need to actually reach out to the executives, so they would be approving those large expenditures.

A really critical job is acting as what we call a senior states person or a relationship manager. Think of all the key stakeholders that are critical that they reach out to, [00:20:00] and especially think about things like employees or employees families, major customers, some of your big investor community groups, your board of directors. Maybe it’s the government officials in your city, the mayor, or maybe even the governor of your state. They are going to be talking … A senior person from another entity wants to talk to the senior person of that company to be reassured and to be told what’s happening, and that’s a key job. Your tactical team can start handing them a list of [00:20:30] people that they need to be reaching out to.

Then lastly, if the situation is really [inaudible 00:20:35] you really want a very senior person at the company who’s on camera who’s actually speaking to the media, because a corporate communications person is not going to be sufficient. That’s the fourth job that they have. I encourage you to think about this, document this in executive plans, and be sure that you actually train them in exercises that this is their job and the tactics are done by the other team.

[00:21:00] Very important roles and responsibilities. But then the second thing is how do you even get started, how do you even pull together and find out that you need to do something? I will tell you when we audit plans this is the number one thing I find missing and probably 75% of ever plan I’ve ever looked at, that all of a sudden the plan is assuming that something magical happened and you activated. But it doesn’t say how that happened, who made the decision, how you came together [00:21:30] and so on. This is really … and then [inaudible 00: 00:21:56] has it been [inaudible 00:21:57] [00:22:00] things that you can do in little tiny exercises to help [inaudible 00:22:04], thus the team is really important.

You first of all have to determine who should be on that actual team, what’s their actual title or role. If they’re usually part of your incident management team or your crisis management team, and it may be the leaders of those four different groups I spoke about, or certainly the key departments. I will tell you that most emergency still [00:22:30] come generally out of about three areas: facilities because of a facility failure or outage, technology because of a technology outage, security is another because of a security related concern or issue, and then many of our clients will add a couple of other folks, maybe the overall incident commander, they might add somebody from HR, and they come together once an incident occurs.

The team’s responsibility is to first of all conduct that initial assessment and they’re using the criteria and the strategies that you have built [00:23:00] to determine whether the plan is going to get activated, and their job is to actually determine as to whether the plan gets activated or not. Any of these members should be able to activate the team and the plan. Note, we don’t say it’s three out of four, or five out of seven, because in some crises there may be just one person standing. Think about an earthquake or something. We’re not going to have to debate. We’re just going to … That person is the only one that arrives on the call, they have the power [00:23:30] to actually activate everything.

The other thing you need to be thinking about initially is with this particular team, how do they connect, what’s the communication strategy, do you use your emergency notification system to send out a message to ask all of them to jump on a bridge. Highly effective, very efficient. We always not just bridges but also we strongly encourage that people have at least a couple of physical meeting places where they might meet automatically because possibly communications [00:24:00] have been hampered. Many times as we know after an emergency the cell phone system is overloaded and we’re not able to actually connect. So having a physical location predetermined is very helpful.

When that team comes together, the first thing they have to gather is what’s called situational awareness. You recall I mentioned that just a few slides ago. This is really important. What do you know? That goes back to how did you learn about the problem? Was it something you saw on Twitter? Was it something [00:24:30] on the news? Was it something that you heard from a police officer, a firefighter, an employee? You basically share everything that you know about the situation.

Then you talk about the impact of what you know. Is it a facility of ours that’s impacted? Is it our other locations? Do we have people that are injured? Do we have our customers or our visitors or our vendors that are affected or injured in any way? Are there impacts to our business, our time-sensitive business processes, and then also consider what are the impacts to the organization. We’re going to talk about impact, [00:25:00] and then what’s the overall effect. Can we work? Can we not work? Can we do what we’re supposed to do for a living? You’re going to have a good discussion about that.

Then also as part of that there’s what kind of event is it as far as the type, and that really is about geographical location. For example, it could be a local event. Maybe it’s only you that’s actually impacted. Maybe it’s actually a power outage that’s only yours, or a fire that’s only affecting you. Very different than a regional event where lots of people [00:25:30] are impacted. A national event, 9/11 is a good example. Even though there were only three physical locations in the United States where there was a physical impact at 9/11, Washington DC, New York, and Pennsylvania, the nation shut down, not only air travel, many telephone carriers were not transmitting communications, and many of our clients closed, that entire day schools closed, the entire nation shut down. Then lastly international, many of our clients are internationally [00:26:00] based and have offices all over the world. It’s not just what happens in the United States. It could be anywhere that something occurs and we may have to activate.

We discover when our team comes together and they share the situational awareness, they talk about the overall impact, they talk about the location. Then we ask them specifically to discuss these five questions. This is what we believe gets to the heart of the matter. We used to have really detailed criteria lists and we discovered that [00:26:30] what people really need actually is the discussion of these five things. People, and you always start with people. Are lives in danger? Is there a life safety issue? Is there an impact to your employees, your customers, your vendors? What’s going on from a perspective of life safety and people? Secondly, what about our facilities? Are they in fact impacted in any way? Our critical infrastructure. Thirdly, what about our technology? That’s everything, our telecommunications, our network, our data centers, is there an information security issue? [00:27:00] We want to drill into that.

Next thing, business. Can we perform our mission critical time sensitive business processes? And does this impact your customers, and does it have a financial impact on your company? If you can’t do what your company is supposed to do, that is a significant issue, and that certainly impacts your business and your bottom line. Then lastly, the fifth one is actually the one that’s probably the most subjective but really important to discuss. Does this [00:27:30] impact, this event impact our organization’s reputation and our brand? Just look at the United Airlines is a great example of that. An event that happened in one small, a regional jet situation in Chicago O’Hare that because of social media had a damaging, beyond damaging effect on United Airlines’ reputation in print.

We often have a little matrix that kind of looks like this. It’s kind of like a bingo box. [00:28:00] Essentially what people do on a call is they talk through the people, facilities, technology, mission-critical activities, and the reputation and brand issue, and then at that point then they call the question. We ask them then and many of our clients have a severity level so they might use have a sev one, two, three, or four, and they go in both directions. Sometimes the sev one in one place is the most critical and sometimes the sev four is the most critical. But we ask them, “Label the event. What is the severity level [00:28:30] that you’re assigning?” That’s helpful because it’s like shorthand, and whatever you use in your company, everybody knows, “Oh, it’s a level two. Oh, it’s a level three. Okay great. That’s helpful because we already kind of have a sense of what that means.”

Then we ask the question, “Does this incident actually meet our criteria for activation?” We make them call the question and we literally would do that on a call. Then if the answer is yes, we are activating our crisis management plan, we are activating our emergency [00:29:00] operations center, which could be virtual, it could be physical. Then once the team is activated that group that met the initial assessment team, they actually fold into the crisis management team because that’s where they belong. Then of course you’re going to be informing your executives that, yes, we’ve activated, and you’re going to give them their first initial briefing because now you know things after you’ve gone through this assessment process.

Now the answer could be no, and maybe what you do after you have this big [00:29:30] discussion and you go through the matrix and you talk through everything, the answer’s no. At that point then you have to determine who on the IAT, the incident assessment team is in charge of actually monitoring the situation, and you want to set an extra briefing schedule because we want to let people know what’s happening, because if it was bad enough for you to get on a call, you should not just go whistling off into the distance assuming that life is great and things are going to be fine. You should make sure that you follow this until it gets resolved [00:30:00] and that we don’t have an issue. You would be using your standard business practices to do that, and we’re not standing up any special teams or activities and the only thing that’s happening is the initial assessment team where the incident assessment team is following it ‘till it ends. Pretty straightforward, really simple. Go back and look at your plans and see if you have some kind of process like that, and if not, consider adding that immediately.

The third thing is developing an incident action plan. This is really important. [00:30:30] This is actually one of the major hallmarks of the incident command system. Now if you never ever use ICS, that’s fine, but this particular process will help you and your company be as organized as possible after any crisis, and it serves as a excellent communication tool to others about what you’re doing and how you’re managing the event.

Let’s talk about this. What’s so great about this particular process called an incident action plan [00:31:00] and why is it better than sliced bread? You know what’s amazing to me is it’s super, super simple. It only has essentially four things. But yet I will tell you that unless people have been formally trained, people don’t do this. This is something you want to make sure that you have in your mobile tool if you’re using a mobile tool, you want to make sure that you’ve got it in your planning process, and that’s something that’s used and it’s shared widely. It only has four things.

First of all, it has the overall status of the event. [00:31:30] In other words, your situational awareness, detailing the history of the situation and what the current status is. Then you have very specific strategic objectives and any other kind of necessary information that supports those. Thirdly, every one of those objectives is actually assigned to a particular person or team, so that if we want to know what’s going on with that objective, [00:32:00] we can literally go find that person and find out. Then lastly it includes the date and the time of the next operational period. What’s that? An operational period is how long your team works on the incident action plan before it comes back and reports status, determines if you have new objectives, and then recommits to the operational period, or actually folds down the process because we’re done. [00:32:30] It’s really simple. It’s really straightforward.

Now in this particular process the IAP should be written, because you want to make sure that everybody that needs to know what you’re doing can see it, and it leads to certainly less communication problems and less confusion. I’ll give you an example, couple of examples of this. We have clients of ours in the Florida region and certainly up the eastern coast and also in places like Singapore and others. In the eastern part of the world of course it’s about typhoons and in the eastern United States [00:33:00] it’s about hurricanes.

If there’s a pre-hurricane alert or a pre-typhoon alert, what will happen is that the teams get together, they develop an action plan, and they actually know exactly what they’re going to be doing. They have their operational periods established and the hurricane hasn’t even hit. So it can be used in a pre-planning process if that makes sense. Certainly it can be used after any incident where if you’re trying to make sure that your additional offices, executives, and other key players know [00:33:30] what your team is working on and who is doing what, it can be shared widely, PDF-ing it and sending it out as an attachment in an email.

How do you actually pull together this thing? It’s super simple but yet I’ll tell you most people don’t do it. What happens after an incident is that everybody’s kind of running around thinking that they should be doing what they think they should be doing, and many times it’s not the right thing, or we have some things that are having a zillion people working on them [00:34:00] and other things that no one’s working on. The assignment part is really important. Just to reiterate this, I want to peel this back just for a moment a little deeper here.

First of all, you want to make sure that you’ve assessed the incident and you have all of the current status available that’s in this report. It could be a paragraph, it could be a little bit longer. Essentially what you want to do is you want to make sure that this information is from a wide variety of sources as we talked about earlier. I can’t emphasize how important this is, and it’s a great exercise, [00:34:30] just even developing what’s your situational awareness is. Practicing where you get your information, how you bring it into your command center, whether that’s virtual or physical, how you display it is it on status boards. Is it somehow captured on a document that you might be projecting by an LCD projector? Do you have it in SharePoint? Whatever the issue is. Then how do you follow things, a lot of traditional media and social media, which as we know is critically important.

[00:35:00] Then after you know what your situational awareness is, then you’re going to establish these incident objectives. Let me just talk for a moment about that. These objectives would be written by each person who’s part of the planning process. So if you’re utilizing the incident command system, that’s everybody that’s in charge of one of those teams, so operations, planning and intelligence, logistics and finance. If you’re using your regular department it’d be the individual assigned for each one of those departments. What are the things they’re working on?

Now the way that we write objectives may sound [00:35:30] a little picky, but I do want to mention it because it’s very helpful. When you write these strategic objectives for your incident action plan, they should be short, they should be concise, and thirdly, they should always start with an action-oriented verb. Okay, that sounds really picky I know, but think about that. If I’m going to assign you a job and I give you a long sentence that sort of drones on and on, you might get to the end of the sentence and still wondering what the job is. If you think about [00:36:00] that in a short concise statement with an action-oriented verb, it becomes very different.

Something might be such as account for all employees, very likely assigned to HR. Conduct an initial damage assessment. Think of that going to facilities. You could have the same thing for a technology, conduct a technology assessment, going to IT. Imagine or develop initial communication points or [00:36:30] talking points. That would go to communications. Think of the things they need to do. Think of it being in a short concise sentence starting with an action-oriented verb. You give that to somebody, you know exactly what their job is because it’s super, super clear.

Then you want to make sure that you’ve actually signed all of these objectives to an individual or team, so that if I want to follow up what they’re doing it’s not hard to do that. Then you determine the operational period, when do you meet again. So if it’s now 12 [00:37:00] o’clock straight at noon, I know that I’m going to work for four hours so my operational period is four hours, so at 4 p.m. we come back together. We do two things: we report status and then we talk about new objectives. That’s what you keep doing until this entire thing is done. Really simple.

Then now that you’ve actually got this plan, you can actually communicate this plan to all of your key identified stakeholders, whoever that is. They can see what you’re doing, they can ask appropriate questions. [00:37:30] But what this does often is it stops a lot of questions because everybody knows what you’re doing, and that’s super helpful as well.

The last one on my list, timely and effective communications. This is one that I see people struggle with all the time, and it’s really sad because it’s actually one that has a lot of solutions around it. Effective and timely communications just don’t happen. They require planning and they require the right [00:38:00] tools. This is not magic. It requires work. It requires planning and you have to have the right tools and you have to have thought this out. What we believe that you need to have these effective and timely communications is essentially three things: you need to have a communications plan that includes authorities, which includes things like who can approve what message and when. If you haven’t got that figured out, you’re going to take forever to communicate. You should have pre-written templates for all the likely emergencies that are likely to happen to you. [00:38:30] Then lastly, you need to be using the right tools to make sure that we can communicate effectively with our key players.

Let’s talk just briefly about a communications plan. The communication plan should really clearly outline three things: who can write communications, who can edit them, and who can approve them. Now that sounds really picky I know, but I will tell you what we often find is that the second two bullets there are the ones that kill most organizations. It may be clear [00:39:00] who writes the communications, is very likely your comms department, but then the question is who can edit them. That sounds really crazy, but I’ll tell you sometimes every person that has some senior title feels like they have to be the person that actually edits it. I want the comma over here, I want a different word here, and they can pick it to death. We’re very clear when we write comms plans about who has the authority to edit anything, and then who can actually approve them.

That’s really important because that’s [00:39:30] a second area where people waste a huge amount of time. We believe that there’s actually three levels of communications for you to consider in an emergency. There’s the emergency communications that are very likely all about life safety and very likely issued by either your security or facilities team. They should be the one that have those pre-written and developed and they should be the only ones that edit and approve them. Because we don’t want to have a meeting to discuss [inaudible 00:39:57] your emergency comms issue that has to do with life safety.

[00:40:00] The second kind of communications that we observe in our client population are tactical ones, and those are usually instructions. Activate your business continuity plans, go to our alternate worksite, call the emergency hotline tonight, listen to your instructions on your emergency notification system, those kinds of things. Again, that should probably have very clear and simple communications about who writes them and who edits them and the approval process should be pretty low on the food chain, probably the manager of a particular [00:40:30] department or a manager of communications.

Where the issues come in for lots of editing and approval is really about strategic issues, and that’s ones where executives very likely are [inaudible 00:40:40] on them and that becomes a longer process. But emergency comms and tactical comms should not be one that gets hung up because we don’t have approval or we have people who are wordsmithing.

The second thing really that’s important is the pre-written communications. [00:41:00] We talk about this all the time, but I will tell you, I don’t often see them, and when I do, which is such a speedy process for people to actually, to be actually able to issue comms. They should be pre-written and they should be approved by whomever needs to do that, whether that’s legal or the executives of whomever. All of those tactical and emergency comms should all be pre-written in advance and all developed and approved without any process at the time.

[00:41:30] You also want to make sure that these templates as I mentioned really are in the three areas that I talked about. Emergency comms, I want all the public address systems, I want all of them, 140 character text written out, whether they go out through your ENS or they’re going out through Twitter or through sending a text to employees. I want to know what the tactical comms are and approved. There’s a lot of strategic comms that you can have basic placeholders that are done in advance and approved that could be sent out to some of your key stakeholders, informing them that you have a problem, you know [00:42:00] you’ve got a problem, and you’re working on it.

Then lastly, what are the tools that you’re using. Gosh, there’s lots of them, but identify what they are and who’s going to use them and how you need to them. Public address systems of course for things like emergency comms, but also voice and email and text and websites, and what about your emergency notification, and all the different ways you can use it, and there’s a lot more beyond this. But think about what the tools are. Who has the authority to use them? Do they know how to use them? Can they deploy [00:42:30] them from their phone? What are all of the things that you want to have in advance so that the comms are not delayed because we don’t have the right tool or we haven’t thought about the right process? So tools are critical. So when you look at effective comms, you need the communication plan, you need the templates, and you’ve got to have the right tools.

Having said all of that successful management of any crisis really requires several key things. It does require these clearly [00:43:00] defined and documented team processes and roles and responsibilities, so start there. You can whiteboard that and understand it and really develop a really solid team with clearly defined roles.

Then you need this clearly defined initial assessment team process, and the actual team itself. You need to have written action plans for any activation that you have because it gives you guidance, it gives you timing, and it makes everybody clear about who is doing what, and we’re all on point. [00:43:30] You have to have the communication plan, the pre-written templates, and all the delivery tools figured out well in advance.

Then lastly, although I didn’t mention this but I think it’s critically important, you’ve got to have the training and the exercises that increase the familiarity and the competency of your team, because if you don’t have this then the problem is going to be is that they’re not going to know what to do. Are you going to have the best plans in the world, you’re going to have the best processes, but if no one knows how to do it, if there’s not sufficient muscle memory, you’re going [00:44:00] to struggle as well. On that note I’m going to pass this back to Will so he can talk about his topics.

William Penfield:

All right. Thank you so much. [inaudible 00:44:12]. Thank you so much Regina for that great presentation. Now I want to take a few minutes to talk about the critical event management process and how it can help your organization navigate through a crisis in tandem with the great [00:44:30] best practices that Regina just set forward.

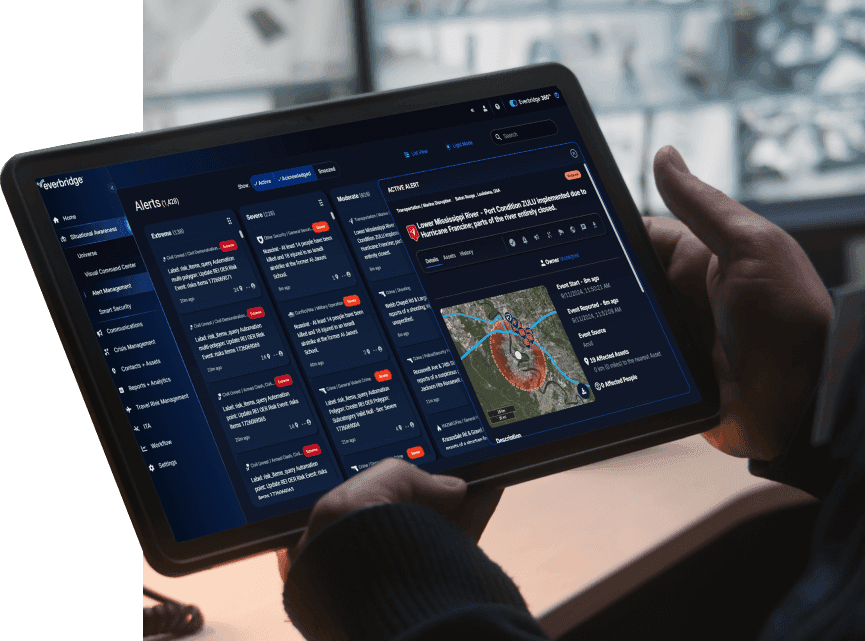

When we talk about CEM we’re talking about a process that helps bring together activities and systems, which are all too often left in silos into a single pane of glass. With CEM your organization can quickly assess events and determine if there is a threat or critical issue, locate the people affected, and who needs to respond based on certification or on call status, automate the process of activating standard operating procedures, [00:45:00] which is where the pre-written templates come in that Regina just mentioned, and communicate instructions for stakeholders and collect information from the field, analyze event and team performance to identify areas for improvement, and lastly, to visualize your key people, assets, and facilities on a single pane alongside current threats.

By breaking down these information silos and inefficient processes used to resolve critical events CEM provides organizations with four ways to improve on these incidents, by reducing the business disruption and [00:45:30] cost resulting from the critical event, providing better visibility to stakeholders and response teams, identifying areas for continuous improvement, and reducing the cost and number of overlapping tool sets across your organization.

Now I’m going to take you through the steps through the critical event managing process and the first step we want to touch on is the assess, so what is happening and what is the impact of the incident. By reducing the number of systems people have to access the time it takes to assess a threat decreases, [00:46:00] therefore minimizing the impact of the threat. To fully assess the situation your organization will need data from multiple sources, including frontline sensors and people in the field, global threat and terrorism event data vetted by security analysts, weather intelligence, and much more.

After the assess threat we move on to the locate, which who is in harm’s way and who can help. In the past utilizing static locations of home and office addresses sufficed. However, in today’s environment [00:46:30] with the rise of the mobile worker, your organization needs the ability to dynamically locate people based on where they actually are, which building they last gained access to by swiping their badge or, which Wi-Fi hotspot they connected to when they logged into the corporate network.

During any crisis it is important to be able to locate the resolvers and responders, the people who are or may be impacted, and the people who have to be informed. In addition to their location, the organization may also need to locate people based [00:47:00] on their certifications, skill sets, and on-call availability, all made possible with critical event management.

Once people are located, the organization should move onto the act phase, which allows you to answer the questions of which team members need to act successfully to get through the crisis. With critical event management the organization can automatically activate your standard operating procedures, which include conference lines can be instantly joined to speed up response, [00:47:30] messages can be automatically triggered, and devices such as siren, the digital sign can be automatically activated. Also, escalation processes are followed so that for example if during an IT outage the primary network engineer does not respond in two minutes, a designated backup is automatically summoned.

Lastly, once the incident is over your organization should enter the analyze phase, which helps you answer the questions which team performed best, which task [00:48:00] took too long, and which resources were missing. By having these detailed data available your organization can identify under performing areas and people based on performance or in critical events, to help understand your response time and your time to resolve, how many times it took people to respond quickly, and how many people responded negatively saying, “No, I cannot take this on,” and help you understand if this incident is like incidents that you’ve seen in the past and what you can do to improve on this incident response in the future.

[00:48:30] Throughout the entire critical event management process communication will be an integral part. This is how your organization reaches out to the employees who may be in harm’s way or simply sends out instructions to what all employees need to do during a specific incident or crisis. By accounting for individual contact preferences they’ll have the best chance for reaching people. For example, an after-hours text will likely be more effective than an email.

[00:49:00] In conclusion, I want to quickly mention that the Everbridge CEM platform is able to address numerous incidents and challenges ranging from a medical emergency to a cyberattack or a supply and chain disruption. Each day we help our 3,000 plus customers, ranging from nine of the 10 largest investment banks in eight of the 10 largest US cities through incidents by enabling them to assess, locate, act, analyze, and communicate to help keep their people safe and their businesses running.

[00:49:30] With that we will move on to our Q&A portion of the session. As a reminder to attendees, you may submit your questions by typing a question into the open text field in the questions panel on your screen. Regina, the first question we have for you is, who are the key personnel that need to sit in on the team for strategic and tactical decision making?

Regina Phelps:

That’s a great question. Part of it depends on your business, but the first thing you want to be thinking about is the [00:50:00] core infrastructure of your organization. For you to be making tactical decisions in particular what you’re going to need immediately are facilities individuals, technology individuals, as well as security so that you can actually have a place to work that’s safe or able to make sure that your employees have what they need. Depending on the incident you might also need individuals that are from key lines of business, communications, HR, and then also things such as legal. You might [00:50:30] need folks from risks to talk about insurance and those kinds of things. If you look at the key departments that you’re talking about, it’s probably somewhere around 20 folks on the tactical side.

On the strategic side, which is really the executives, it really depends on how you define executives. I say that because sometimes I see executive teams that are huge, like 20 people. Probably the most effective ones are probably what I would call more the C-suite probably somewhere between five to seven people, [00:51:00] and depending on the organization, some of our larger clients, maybe 50,000 employees or more, the CEO isn’t even part of that conversation, it might be headed up by the COO or some other individual like that, but it’s really understanding the broad strategic aspects of the business. We want very senior individuals at that level, and again, they’re really dealing with those four things I spoke about, strategic policy, approval of funds, senior relationship management, and media. [00:51:30] They may have a variety of people that assist them, but they really are working on those big strategy issues.

From a tactical perspective look at your key major departments. In some organizations it might be as many as 20 people, maybe more. Then for your tactic, your strategic team you’re looking at that C-suite, the CIO, the CFO. The CFO, kind of all of the Cs, [inaudible 00:51:57] ideally as well because of the cyber related [00:52:00] issue and making sure that they again have those four skills that I talked about earlier.

William Penfield:

All right. Thank you Regina. We have a question from Matthew in the audience that I can take. It’s, “When trying to locate employees, is there an app that an employee has on their mobile device that will update their location of employees in different markets out in the field that may cover different cities and states?” Matthew, we do have a mobile application that allows people to check in and update their location in two different ways. They can either do it manually or you can [00:52:30] set the check-in functionality to automatically update based on a set time interval. That app also for your people in the field, it has SOS functionality, so if they ever find themselves in trouble, they can quickly hit the SOS button and it will send a notification to your security team or whichever team you have on the other end, letting them know that they need assistance.

Second question we have for you Regina is, “Do you have any recommendations for convincing executives to implement a crisis to management team?”

Regina Phelps:

[00:53:00] Oh gosh, that is such a great question. I’m doing an exercise for somebody right now to prove that very point. One of the things that I would suggest that you do is this, is that you look at your first of all your risk profile, what are the things that are likely to happen to you at your location. A couple things. Look at the risk profile, but also I would also encourage you to consider doing some Google Alerts. I love Google Alerts and if you don’t use it, you should. You could actually put the type of business that you have. So let’s say it’s a manufacturer, [00:53:30] maybe you manufacture widgets. You put widget manufacture in your Google search and then you put in other keywords, crisis or disaster, or maybe knowing your risk profile, floods, earthquakes, whatever, and then all of a sudden what the great thing is about Google Alerts is that mama Google every day will send you a digest of all the things that are applicable to you in that particular search.

Then you can begin to build a case about what’s happened to other companies who are like yours and the disasters that [00:54:00] they may have suffered. That’s a great way. Then you can basically sort of covertly send that to your key players to let them know that these things are going on, and “My gosh. The same thing could happen to us.”

The other thing I would encourage you to do is if at all possible do some short, even a really short, short, short exercise for your senior executives, demonstrating to them the importance of a crisis management team. I’m actually doing an example of this exact same thing, is I’m [00:54:30] doing an exercise for a client of ours in Texas next month, and I’m selecting a tornado. There in Tornado Alley. It’s the absolute perfect thing. They don’t have a crisis management process at all, and we’re just going to have an earthquake … having a tornado hit their building. Then the next questions are like, “Well, now what?”

Then going through the issues of talking about the damage, talking about the impact to employees, talk about the fact that their data center is down, talking about the website, “Okay, now what are we doing,” and demonstrating to them that this could happen to you and if you are flat-footed, [00:55:00] what’s going to happen to your company, who’s going to communicate, and what if your data center does go down and your website goes down, and people can’t find you, and how do you serve your customers, and the list as we all know on this call is endless. Sometimes having a short tiny exercise can be one of the best ways to prove to someone that they actually need to take this seriously by developing a team and a process.

William Penfield:

All right. Thank you Regina. A question from Dave in the audience that I can take is, “Have you integrated [00:55:30] with an identity management system or event logging system?” Dave, Everbridge does have an open API for these types of integrations. Some integrations I can talk about is we integrate with access control systems like Linnell, travel booking systems like Concur, and we also have a partnership and integration with International SOS. Next question for you Regina is from Phillip in the audience is, “How often should plans be tested?”

Regina Phelps:

Great question. The general rule [00:56:00] is of course once a year, but I would say to you in a dynamic environment they may need to be tested more often. Let me just say that when we do exercises, you might want to do really one good robust exercise a year, but our brain sort of forgets what we last learn and so we often encourage our clients to create what we call ripped from the news exercises. What does that mean? This can be something that’s really simple. You flip through any newspaper of any city in the world and you’re going to find probably an exercise [00:56:30] on every other page.

So whether it’s the act of shooting a situation, it could be a terrorist event like happened unfortunately last night in the UK, it could be a flooding situation, a power outage, an earthquake, the list goes on and is endless, and you can say, “Pull together your team very quickly.” Maybe it can just be over in the part of a regular meeting and say, “Okay, this thing just happened to us. Who’s our assessment team? Okay, let’s talk about how we would assess it? What do we need to know? Let’s make some decisions. Okay, great. Then the next thing is let’s build an action plan.” You can do a simple exercise like that [00:57:00] with very little planning to be honest with you. If you did that once every quarter and you spent 30 minutes on it, my goodness, your team would be better.

One really good well-thought-out exercise on an annual basis I’d say is a minimum, but try and to do small abbreviated experiences to build muscle memory in your team so when something happens they actually can stand up and do it.

William Penfield:

All right. Thank you Regina. It looks like we have time for one more question. It’s [00:57:30] actually one that a couple people in the audience have asked is, “Who would be on the IAT team?”

Regina Phelps:

That’s a great question. In the IAT which again is the incident assessment team it’s very commonly facilities, security, technology, because those are where the most of your incidents will come from. Then you might have your incident commander or the person in charge of your tactical team. Then depending on your business you might have [00:58:00] one of your most significant business lines, for example, or you might have folks like HR. Just know that you want the team probably to be somewhere between five, six, seven people perhaps, no more than that, and if you need another subject matter expert you just bring them in.

Imagine that let’s say the way that the IAT would work is that events go along in their normal pattern. You have a facility outage. It gets reported along its normal route or technology outage. It gets to a [00:58:30] certain amount of impact where things are down, people aren’t able to work, building may not be available. It trigger, it should immediately trigger the initial incident assessment team and member to go, “Oh my gosh, this is bigger than a breadbox, it’s actually impacting our business. I’m going to call to get an IT.” They all have the ability to do that. So if it’s a technology outage and we realize, “Oh my gosh, we’re not able to process claims,” if you’re an insurance company, or you’re not able to answer calls if you’re a call center, something like that, you immediately send out a [00:59:00] notification on your emergency notification system to your members of your IAT. They get on the bridge.

What happens then is maybe it’s five individuals. You realize, “Oh my gosh, we don’t have a key member of the business available on this call,” and so you reach out immediately to somebody that’s probably part of your greater crisis management team from the business, bring them in because they need to participate based on the outage that you’re having. You have a conversation and you go through those, all the issues of situational awareness, [00:59:30] and then what you want to do is you want to go through the five things I mentioned. Does this impact people? Is this impacting our facility? What about our technology? Are our mission critical time sensitive business processes at risk? Does this impact our brand or reputation? Then you have a discussion about those five things and then you call the question, “Do we activate or not?”

It’s pretty simple and I think what I would encourage you to do is sort of line this out on a whiteboard, whiteboard activity as we like to call it, and then practice it. Then if you realize, “Oh gosh, we need another person,” or maybe that we don’t need this [01:00:00] particular person that we thought we did, then adjust accordingly. But take time to figure it out and then practice it.

William Penfield:

All right. Thank you Regina. I also do want to mention that we will be sending out a copy of the slides and a recording in the next couple of days. With that I do want to wrap up here because we are out of time. I want to thank you Regina for a great webinar and all of our attendees who were able to join us today.

If you haven’t already, please take a moment to follow us on Twitter @everbridge and join [01:00:30] our group on LinkedIn, Everbridge Incident Management and Emergency Notification Professionals. For those of you interested in requesting a one-on-one demo of Everbridge or to learn more about critical event management, please visit everbridge.com/request-demo. Thank you all again for all coming online today and we hope to see you again soon. Have a great day.