Workplace violence is a significant concern that affects employee well-being and safety as well as the overall success of a business. According to statistics from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), workplace violence impacts over 37,000 US workers each year.

This issue not only poses severe consequences for all employees but can introduce hefty costs for organizations. In addition, organizations must ensure they are compliant with all laws and regulations.

As employers, it is crucial to prioritize the safety of employees and take proactive measures to prevent workplace violence and maintain operations.

Here are 9 practical strategies to ensure safe workplaces and reduce the risk of violence.

1. Create violence, harassment, and bullying prevention policies

Establishing comprehensive policies addressing violence, harassment, and bullying is essential. These policies should clearly define unacceptable behavior, provide guidelines for reporting incidents, and outline disciplinary measures.

By establishing a zero-tolerance approach and communicating it to all employees, organizations can foster a culture of respect and create a safer work environment.

Regularly review and update these policies to ensure their effectiveness and alignment with evolving workplace dynamics.

2. Implement training and awareness programs

Training and awareness programs play a crucial role in preventing workplace violence. These programs should cover topics such as anti-bullying strategies, conflict resolution, mental health awareness, and the five types of violence (criminal intent, customer/client, worker-on-worker, domestic, and ideological).

By educating employees on recognizing warning signs, managing conflicts, and promoting a culture of non-violence, organizations can empower individuals to respond effectively.

Offer periodic refresher training sessions to reinforce these principles and provide employees with the tools to de-escalate potentially volatile situations.

3. Establish clear reporting procedures

Employees need to feel confident in reporting incidents without fear of retaliation. Employers should establish reporting mechanisms that ensure trust, confidentiality, anonymity, and a commitment to addressing concerns promptly.

It is crucial to communicate these reporting procedures clearly to every employee, making them aware of the channels available and emphasizing that their safety is a top priority.

Provide multiple avenues for reporting, such as anonymous hotlines or online reporting systems, to accommodate different preferences and comfort levels.

4. Enhance site security measures

Implementing security measures can significantly help prevent workplace violence. This includes visitor access management, video surveillance systems, security guards or patrols, entry systems (such as key cards or pins), and panic buttons.

By having these measures in place and integrating control center systems, organizations can deter potential threats and provide a sense of security to employees.

Conduct regular assessments of security protocols to identify any vulnerabilities and make necessary improvements to ensure an effective security infrastructure.

5. Perform regular risk assessments

Regular risk assessments are vital for identifying potential areas of improvement. Assessments should evaluate training completion rates, adherence to policies, and any gaps in preventive measures.

By conducting thorough risk assessments, organizations can proactively address vulnerabilities and take corrective actions to enhance safety protocols.

Engage employees in the risk assessment process by soliciting their feedback and observations to gain valuable insights into potential risks and implement targeted interventions.

6. Use communication channels to ensure employee safety

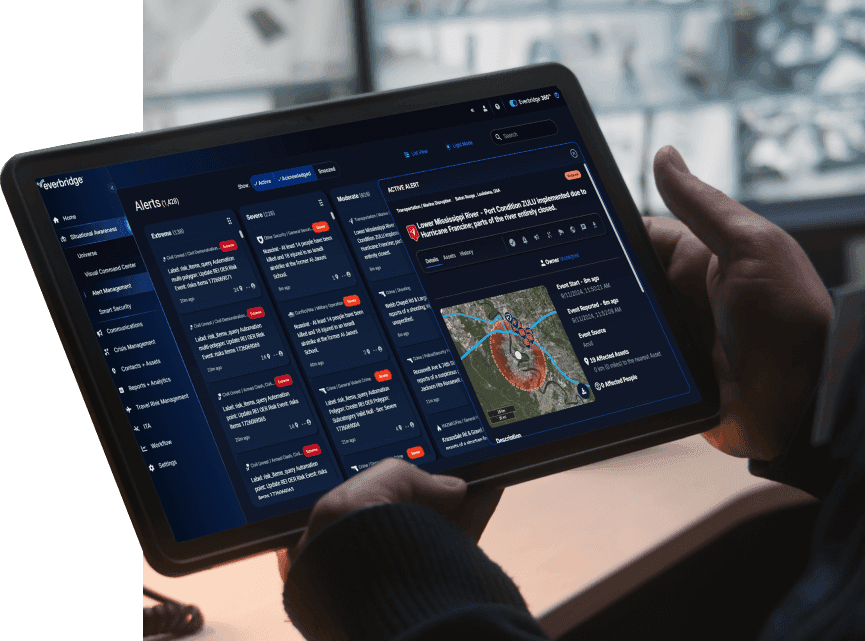

In dangerous or life-threatening situations, effective communication channels are critical. Employers should utilize emergency communication tools and systems to disseminate timely information to employees.

Emergency notification systems, mobile apps, or panic buttons can be employed to quickly alert and guide employees during crises, ensuring their safety.

Conduct regular drills and simulations to familiarize employees with emergency procedures and test the efficiency of communication channels.

7. Maintain a healthy workplace

A healthy work environment contributes to overall employee well-being and reduces the likelihood of violence. Organizations should foster a professional and caring workplace culture that promotes open communication, work-life balance, and professional development opportunities.

Implementing employee well-being programs and providing resources for mental health support can also contribute to a positive and safe work environment. For example, offering counseling services or promoting mental health awareness campaigns.

Encourage open dialogue, establish employee assistance programs, and offer flexible work arrangements to support a healthy work-life balance.

8. Conduct post-event analysis

Following any workplace violence incident, a thorough post-event analysis is crucial. This analysis involves assessing the reasons behind the event, identifying any system failings, and determining what preventive measures can be implemented to prevent similar incidents.

By learning from past experiences, organizations can adapt policies and prevention methods to strengthen their overall safety protocols. Involve employees in the analysis process by encouraging them to provide insights and suggestions for improvement.

9. Comply with laws and regulations

Organizations must stay up-to-date and compliant with all new laws and regulations, such as Senate Bill 553.

SB 553, signed into law in California, mandates that employers take proactive measures to prevent workplace violence. It outlines specific requirements for developing and implementing comprehensive workplace violence prevention plans to safeguard employees from potential threats. It also mandates that businesses must begin complying with the law on July 1, 2024.

Learn more about how Everbridge can support your organization in complying with SB 553.

Build resilience against workplace violence

Preventing workplace violence is an imperative responsibility for employers. By implementing preventive measures such as comprehensive policies, training programs, effective reporting systems, security measures, regular risk assessments, communication channels, and maintaining a healthy work environment, organizations can significantly reduce the risk of workplace violence.

It is vital to continuously evaluate and improve preventive strategies to ensure the ongoing safety and well-being of employees. Together, we can create workplaces where employees feel protected, respected, and can thrive without the fear of violence.

By prioritizing safe environments, employers demonstrate their commitment to employee well-being and create a foundation for a harmonious and productive workplace.

For more specific information on active shooter preparedness, download the Active Assailant Preparedness Report to learn from over 800 organizations on this important topic and how to do better to keep your people safe and organization running.